Stories That Stay

Episode 7 - Dr. Darryl J Ford

Subscribe Wherever You Get Your Podcasts

About Our Guest

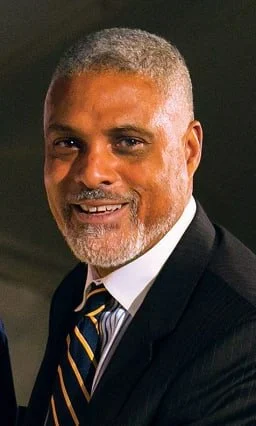

Dr. Darryl J Ford

Dr. Darryl J. Ford is Vice President of Education Leadership Services at Carney, Sandoe & Associates, where he leads executive searches, mentors aspiring leaders, and supports educational organizations through transitions and strategic initiatives. He previously served as Head of School at William Penn Charter School in Philadelphia from 2007–2023. A graduate of Friends Select School, Dr. Ford holds degrees from Villanova University and the University of Chicago. He lives outside Philadelphia with his wife, Dr. Gail Sullivan, their dog Nova, and Alvin, their youngest son’s horse.

About Our Hosts

Shamm Petros, Senior Director of Learning & Development at Lion’s Story, brings training grounded in the organization’s 35+ years of racial literacy research and a story-forward approach to racial healing.

Dwight Dunston, a mindfulness practitioner and storyteller, provides the emotional grounding and reflective prompts that model racial stress processing through the body.

Full Episode Transcript

Dr. Darryl Ford (00:00)

And so you said that I have self-talk. I'm like, yeah, I had self-talk. No one else was talking about self-talk. And so if you are self-talking as a child in the late 60s or mid early 70s, you think you're just crazy.

Shamm Petros (00:27)

Welcome to Stories That Stay, how stories of identity shape us. This is a podcast where healing happens at the intersection of art, science, and storytelling. I'm Shamm Petros.

Dwight Dunston (00:38)

and I'm Dwight Dunstan.

Shamm Petros (00:40)

This podcast is a project of Lion Story.

Dwight Dunston (00:43)

Our guest today is Dr. Darrell Ford. Dr. Darrell J. Ford joined Kearney Sandow's and Associates as Vice President of Education Leadership Services after three decades of leadership in private schools. In addition to leading executive searches, Dr. Ford helps advance new initiatives to support leaders through transition, mentor and train aspiring leaders, and advance the social impact for educators and students across a wide range of educational organizations.

Before that, Dr. Ford served as head of school at the William Penn Charter School in Philadelphia from 2007 through 2023. The graduate of Friends Select School in Philadelphia, he earned a BA in honors, liberal arts, and a BS in social studies education from Villanova University. He holds an MA in educational administration and a PhD in educational administration, institutional, and policy studies from the University of Chicago.

With two college age children, Daryl and his wife Gail Sullivan in OBGYN are now left to their own devices at their home outside of Philadelphia with their dog Nova and Alvin, their youngest son's horse at a nearby barn.

Shamm Petros (01:56)

So as we arrive today with today's guests and his stories, let's prepare ourselves for the feelings, emotions, and truths that will emerge. Wherever you are listening, if you are walking, driving, resting, cooking, cleaning, or laying down, we invite you in this moment to take a few breaths. Just for you, I won't prescribe a breath, but the invitation is to notice your breath and create space for maybe a deepening of your breath

Dwight Dunston (03:07)

Welcome, Dr. Ford.

Dr. Darryl Ford (03:09)

Well, thank you. Thank you for that welcome. Thank you for that incredibly gracious introduction. I also want to thank you for that moment of settling in, breathing, settling in, finding something in silence. I'm thrilled to be here and we'll see where this goes.

Dwight Dunston (03:29)

Wonderful. Yeah, it's such an honor to be in this space with you and to be in the presence of a fellow Quaker School alum. As someone who also went to Quaker School, we always like to start our conversations with our guests by just asking you to share how you're arriving today and on a scale from one to 10, with one being not stressed at all, 10 being very stressed, how you're feeling about sharing your story with us today.

Dr. Darryl Ford (04:00)

I think I'm feeling about maybe a four. I'm not feeling much stress, but I have engaged in some activities today that are not work related. And so of course, when you do other things, there's the push of the work that you're not getting done. So I started my day on a work call and then I visited a senior living facility with a friend who I'm trying to help figure out where she might live, a friend from church. So I feel good about that. And yet, you know, every moment.

that you are doing one thing, there's an opportunity cost of not doing something else. And so my inbox is full, so I'm feeling a little stressed. I have a writing deadline. I need to present something tomorrow, a tribute to a friend. So I'm feeling pretty good. I'm feeling like this conversation, I hope it's gonna be a 10, not on your stress meter, but a 10 on like a good thing meter. But I think stress is a four, but it's not bad stress. It's just like, I can't get everything done that I need to get done.

Shamm Petros (04:57)

Thank you, Dr. for answering that. We'll ask you that again at the end of this to see how the experience really is with sharing your story. Dr. Ford, you are no stranger to our work. You're no stranger to the work of Dr. Howard Stevenson, science story. So I know you are familiar with these questions. These questions we ask people that seems to stir conversation or least reflection. That is the nature of our discussion today. We're going to ask you to reflect on. their earliest memory of race or difference that you recall.

Dr. Darryl Ford (05:31)

Thank you for that question. And I've been thinking about that. Is this a memory of race or difference or something at the intersection of both? And the answer probably is yes, the latter. But the memory that I want to speak about and think about for a few moments really is a memory from childhood and a memory of education. Education has been so central in

my life and in my family's lives. My mother and father were both first-generation college students, trained to be teachers and had careers in education and in other sectors. Back to my grandmother who died when I was very, very young, but her father saw fit to send my grandmother, his daughter, to a private school for girls in New Jersey. She grew up in Virginia.

And yet this black woman had a private school experience, a school whose name we probably don't even know anymore because all those schools have closed. Her father saw fit that his daughter was going to be educated. And our favorite cousin was Mama Irma. Mama Irma died maybe about eight or nine years ago. Right before COVID, I think she was 104 and living on her own. But Mama Irma was a teacher.

She was a teacher and even after she retired from her career, she was still supervising student teachers well into her seventies and late seventies she was supervising teachers. And so my first memory of difference or a memory of difference really was about my own childhood education where my parents saw fit and we were fortunate to go to a progressive private school outside of Philadelphia.

where learning was out in the woods. It was experiential. This is the late 60s and early 70s before I went to Friends Select School. That just was not the experience of the other people who lived on the block. You know, I think maybe my brother and I, we went to this little progressive school. There was one other neighbor who also went to that same school for a while, but everyone else was going to public school and everyone else was going to Catholic school.

When I left that school and went to Friends Select in fifth grade, my school experience was so different. You couldn't be outside playing. All of our time was in class at school and then activities after school. And so by the time you got home late at night, then you were doing several hours of homework. And so you just weren't outside. Before that experience, I think when I was a child growing up in Cobb's Creek,

I didn't feel like the rest of the kids. I felt like I was an outsider. I felt like they made fun of me for how I spoke or where I went to school, places that they had never heard of. It really situated yourself as kind of being other. I don't think I felt any harassment or sadness that would be any different than probably any kid growing up, but I did feel like I was different and my experiences were different.

As I got older, I remember myself immersing myself in books and reading all the time outside of what I needed to read for school. I remember reading stories of people who would be my heroes, like Frederick Douglass, and thinking about what they needed to do to break out and to be different and to change things.

I kind of immersed myself in these heroes of yesteryears, Harry Tubman, people like that. And that became my community when in fact I perhaps did not have a community of kids and friends as I wanted that to happen on the street. And again, this is not to say that anyone was unkind or not, maybe it was just me, but my educational experience was so different than everyone else's that

I remember it and it still sits with me.

Shamm Petros (09:48)

And it's like a sea of memories. You started with the grand story of education and how it looked throughout your family, and then your story, which people quite often do. I have a few curious questions, but I'm going to, Dr. Ford, now ask you a series of questions that are really around mindfulness practice, right? And we're just trusting that in this practice, we'll get more data. We'll understand our stories at a different vantage point. First, thank you for sharing. It is very vivid.

And you might feel like some of these questions will make it even more vivid. But as you share that narrative, and there's a couple in there, right? But I'm really maybe pinpoint you going to the private progressive school outside of your community, having a different experience than the people on your block. And then again, fifth grade, you transitioning into friends, community schools that also feeling like, I'm different, I'm other. As you reflect on this, what are the emotions? If you can name feelings, not thoughts. the feelings you have around us.

Dr. Darryl Ford (10:49)

I think there's a little feeling of sadness, but not huge sadness.

Shamm Petros (10:57)

With the little feeling of sadness, can I ask you to put on a scale, one to 10, 10 being is extremely sad, one being not so sad. How many understand that little?

Dr. Darryl Ford (11:08)

Three.

Shamm Petros (11:09)

any other emotions, and if you can scale those as well from one to ten.

Dr. Darryl Ford (11:14)

a little bit of excitement and that probably would be about a six. I don't know if I'm feeling or inarticulating any other emotions, but those would be the two.

Shamm Petros (11:25)

Yeah, and I'm reflecting back there maybe is, I would say there was some pride because you tied in your that moment, those moments with the grander moments of your grandmother and elders. Do you think pride is there in the story? And it could be, no.

Dr. Darryl Ford (11:40)

Yeah, I mean, think there's some pride and yeah, clearly some pride and clearly some survival. I don't know if survival is an emotion, but it certainly is a state of being.

Shamm Petros (11:50)

Can you scale that? Is it scalable for you?

Dr. Darryl Ford (11:54)

Pride would be like an eight or a nine.

Shamm Petros (11:58)

I like making up feelings, so I survived could be a feeling. I'm sure there's a better word. And I always find English limiting. Yeah, I survived. Can you rank that?

Dr. Darryl Ford (12:09)

That'd be about a seven.

Shamm Petros (12:11)

Beautiful. So we have existing in the same time, some sadness and excitement. You said a little for both, but it's helpful for us to know. Sadness was around a three, excitement at a six. And then also pride, living somewhere between eight and nine. I survived that at a seven. These feelings, at these numbers and maybe others you can't articulate. Do any of these emotions come to life to you in your body right now? Do you feel it in any way?

Dr. Darryl Ford (12:39)

I am not feeling these emotions in my body, perhaps because of my understanding of Dr. Stevenson's work and using his work in some of my strategies when I was a head of school and having experienced some real stressful situations, racial stress, other kinds of stress. I know what that felt like in my body and I'm not having that in part because I'm not feeling it.

And secondly, this part of my life, while I'm happy to talk about it, this may be the first time I've ever talked about it, this part of my life has been contained and reconciled. And so it's not like a new punch of an offense or something. And so I'm feeling pretty all right.

Shamm Petros (13:28)

And thank you for that distinction. In practicing this work, you've been able to notice your body, particularly when, say, there's high stress, even if you're managing the stress, right? When you're on guard, when you're vigilant, when you're managing crisis. But this story is different. This is a story that holds a lot of both and emotions, pride and sadness, excitement and survival. I want to follow up with this question, which I naturally hear already.

As you reflect on these memories, particularly the moment realizing I'm other, I'm different in these education settings, did you then or now have any self-talk, any messaging you tell yourself inside or outside or otherwise?

Dr. Darryl Ford (14:14)

And that's a great question. do think, yeah, I had a lot of self-talk. I had a lot of self-talk because one, it is how I learn and how I remember things. Because I had great parents who made it clear no matter what others were doing or saying about you, you are worthy. And so that was in my head all the time. Three, because if there was a moment of conflict or confrontation,

For me to be prepared for that moment, I had to practice, practice. What I find really interesting about your question of self-talk, this conversation and what we do in schools today and the framework that Lion's Story has helped develop gives people a mechanism. And so you said that I have self-talk. I'm like, yeah, I had self-talk. No one else was talking about self-talk.

And so if you're a self-talking as a child in the late sixties or mid early seventies, you think you're just crazy. Now we know these are strategies. Even with great educators around me and great parents around me, no one was talking about self-talk. I think about, you my brother and I were very close. I think as children, we had very different interests and we really got along, I think quite fine, but they were brotherly moments.

And I think about my mother who would leave, maybe leave us maybe for one hour, two hours, one Saturday a month to walk two blocks around the corner to our church to do some volunteerism. And we were there together and my brother and I must've been tussling getting into it. I would talk out loud. This is what he did to me. And mom, what are you gonna do about it? Cause I had to practice it. Of course, him being the older brother,

And because our bedrooms, there was a door between them, but no door. You just walked in and out. He heard me. He heard all that self-talk. When my mother would come home and I would say, this is what he did to me. He already had a retort because he heard my self-talk. So there's a lot of self-talk.

Shamm Petros (16:28)

And that is hilarious. That was like a meta self-talk analysis. And it makes sense. You're such an orator. You know, I don't know anyone that has met you for longer than a minute that would say otherwise. And I would say, although you named this beautifully, the cultural perception of people that did self-talk versus now, but I do think it is genuine to a lot of cultures. Even like when we look at black American culture and all these parables and idioms and sayings that literally

travel across time and space, right? We all end up saying the same things to one another in the good space. But your mom offering you this self-talk with your deserving doesn't matter what people say about you. And sometimes it's hard to parse out because it's so ingrained into us. Like we think these self-talks are just truths, but they are actually affirmations, they're prayers. And your story is actually really funny because your form of fighting is the verbal protest too, like all in one. That's very, very magical.

Dr. Darryl Ford (17:27)

We have self-talk as a concept. We've just been talking about that. We have practice as a concept, you know, of how do you confront the bully. There were bullies because I was in my room self-talking and the next door neighbors could hear it. I love music and I would get off at the, from the L and walk home every day in my head, music was playing.

And sometimes I'm conducting as I'm walking down the parkway. You know, that doesn't make for easy, I want to be his friend because I'm a music person too. It makes for look at that strange kid over there. We have these frames today, these strategies, even this notion, how are you feeling is a three or a 10. All of this helps.

Shamm Petros (18:18)

That's so key to liberation. For you to be in those moments would say your music coming back from school, you're creating worlds of your own that protect you, that help you feel prepared for the next day. Right now for me what's coming up is you befriending the likes of Frederick Douglass in your bedroom. Of course you would as a person that valued the word and word so much. Frederick Douglass himself an example of.

how education setting really transformed him. And I want to ask this follow-up question. The imagery around your practice of self-talk is so vivid. Do you see any images when you look back at these memories? You described many. Are there any other vivid images coming to you as you reflect in this process?

Dr. Darryl Ford (19:05)

Answers yes. And the images really are of two, two sorts. It's the Harriet Tubmans and the Frederick Douglases and the James Fortons of the world and me learning about all these people, hoping that I might have the fortitude of those good folk. And the images are also of these beloved ancestors.

You know, my mother and my father of our cousin, Mama Irma, of people whom I never met. My grandmother who I met, I don't have much of an image of her. My images probably come from family photos, but I have quite frankly, the protection, the smell of my grandmother. I can remember my grandmother and me being three years old.

And her, her holding me and what she smelled like. can remember that the candy she gave me and my grandmother's father, whom of course I never met. If my grandmother was born in 1895 or wherever she was born, her father, who knows when he was born, but the fact that he had the strength to operate outside of a system and to get his granddaughter.

Dwight Dunston (20:07)

Mm-hmm

Dr. Darryl Ford (20:29)

a private education. ⁓ So those are the images. It's kind of this notion of the ancestors sustain us. And while I love that, why do we always have to call upon the ancestors? Shouldn't this be all better today?

Dwight Dunston (20:46)

I'm just feeling the pride and gratitude in my own self. It's sort of in my heart. It's in my eyes as well. Next to that is grief and gratitude as I just think about loved ones. But so much pride in my heart at eight as you share your story. Just thinking as we move to a close of this conversation, so much of the work that you do in the world.

today now is supporting educators, school leaders in programmatic ways and mentorship ways to really be beacons and mirrors and windows for the school communities they're a part of and especially the young people that are part of that those schools, right? Having been in the positions you've been in at schools and now it's, you know, you're not in the school day to day, but I imagine part of your work is visiting schools and seeing

ways you can support the adults that are part of that community to be these figures in the young people's lives that they're around, that so many of the people you named, they were your family, they carry this responsibility. And I think a lot about teachers and educators is we're not the parents, right? Teachers, staff, know, principals, not the parents, but they're walking lockstep with the dreams that the parents hold of helping to nurture young people into

becoming who they are to become, becoming the best version of themselves. As you just think about the role that you hold down professionally and personally and in the communities you're a part of. I'm curious about the feelings that come up when you think about your sort of professional responsibilities around your role. And then any words of wisdom that you just carry with you from these staples in your life.

Whether it's family or the Frederick Douglases or the Harriet Tubmans, these people you've really walked with as well in your life that have accompanied you, shaped you.

Dr. Darryl Ford (23:03)

I think the feeling of pride is pretty strong, pretty high, maybe an eight. Yet I think that feeling of an eight is because in some ways I've stepped away from practical administration after 31 years of being an administrator. I think we feel pride when you're doing the work, but you're in the middle of the work. There's not time for reflection. You're in the middle of it.

It's crises after crises and it's creating opportunity after opportunity. And then the world has a pandemic and then the world goes crazy in certain ways. So you're in the middle of it all. Stepping away from practical administration, direct administration, I can feel innate, think, because I hear readily, this is what you were able to do for me. This is how you helped me. Thank you.

Dwight Dunston (23:59)

Hmm

Dr. Darryl Ford (24:01)

Dwight, from that question of what is the feeling to your second question to what advice, I wonder if we would all be more gracious and filled with opportunity if we could somehow separate the busyness of the work, which is important. Work is important. If we separate the busyness of the work from

the gratitude and maybe a better way of saying that is we could add the gratitude onto the busyness of the work. So maybe that's the advice. Don't forget the moment and let's be thankful. And then the other piece of advice, which my brother and I learned so clearly from our parents is you always want to be of service. You always want to be of service to others. And whether that was shoveling the snow on a row house block where there were, I don't even know, 30 houses on one side of the street and 30 houses on the other side of the street. And we would just go up and down our side. didn't cross to the other side, but we'd go up and down our side, shoveling the snow or whether it was driving someone somewhere when we began to drive because we could drive and we had a little raggedy piece of a car or whether it was.

That was our car, my brother and my car, not my father's car. Our car was raggedy, my dad's car was good. Or whether it was going into someone's home and playing their piano, which had not been played for years. But how could you be of service and lift other people up? How can you lift other people up? And so those might be several pieces of advice, a place to begin.

With a few words of advice.

Dwight Dunston (26:04)

And I wanna just invite our listeners, and you as well, Dr. Ford, actually invite you and our listeners to take a breath in on those pieces of advice, of wisdom, of remembering the gratitude as best as we can when we're in the moment and to be of service. Just a moment to just breathe on those.

I just feel lot of warmth and openness just in receiving those and people are coming to mind who who model that really well, being gracious in the moment, who model, who just model being of service to the communities they're a part of. Yeah, let's just take a moment to just let those pieces of wisdom rest with this audio reprieve and inviting you Dr. Ford and our listeners to just breathe in once again with intention, with care. Notice how the stories have been sitting with you from Dr. Ford.

And as a way to close, Dr. Ford, curious how you're feeling after sharing your stories. You were mentioned being at a four as we began. Has that number shifted, moved for you?

Dr. Darryl Ford (28:10)

I think I'm probably at about a six or a seven. I think I feel no more or no less stress. This was not a stressful encounter, but one never knows what is going to come out of my mouth. So I feel pretty satisfied that

Perhaps there might be a few words in here that resonate with others. And so I don't want to feel fully satisfied. I feel pretty satisfied. 607.

Dwight Dunston (28:40)

Nice. Love it. And we often like to say if it is available to you to ask our guests to just, if they had to give a hashtag or a headline of the stories they share. And I know you had a few different vignettes for us here, but if you had to put the things you shared into a Google Doc and give it a title, or if you were about to write a book based on what you shared today, any titles coming to mind?

Dr. Darryl Ford (29:09)

Be of service and whatever you have and can, give it away.

Shamm Petros (29:26)

Dr. Ford, that really aligns with your commitment to the processes of life, which is the service, even though we don't know if it's gonna come out the other end, right? Speaking the truth or commitment to the word, because the commitment's there, even through times of changes, interpretude, I see that. And I have excitement at like a 12. I mean, I believe in the first like 10 seconds you start sharing, I was like, oh yeah.

This always works. Like your first stories always just make so much sense. You just make so much sense into the blueprint of how you've oriented yourself. And that's just from the little that I know you. You share you're doing some hard things, some generous things today, tomorrow, this weekend. I could tell in how you described some of the hard things you're doing that your commitment to the word is very powerful. So I hope at least this process you can just maybe give to yourself.

the next couple of days is just check in, you know, because you might be very comfortable in a place of high pressure and stress, but what does it really mean to feel that body, your body in that moment? What does it mean to even speak to it, the imagery, the self-talk, even the emotions? And what if those are the words? So I hope you can use that, this mechanism, whatever lingers with you from this conversation. Thank you for your time. ⁓

Thank you so much for tuning in to Stories That Stay, How Stories of Identity Shape Us. This podcast is a project of Lion's Story. To learn more about Lion's Story and our work, visit lionstory.org. This episode was produced and edited by Peterson Toscano. Music during our mindful moments come from Dwight Dunston. Our music also comes from epicsound.com. For our listeners, know that we are here to help you build a real courage, practical language, and skills to navigat

Stress, discomfort, excitement, whatever may be, with more clarity and compassion, starting with yourself. If you found value in today's episode, please consider leaving a review, subscribing, or sharing this with someone who needs it. Your support helps us grow our healing community with practical learning resources and training, opportunities for individuals and communities that need it the most

Dwight Dunston (31:40)

And until next time, keep listening, keep learning, and keep telling your story. And remember, remember, remember, you are your most important listener.

Learn More & Resources

Visit Lion’s Story to explore our mission, training programs, and upcoming events like the

Resilience Literacy Institute.

Stories That Stay is a project of Lion’s Story, a nonprofit dedicated to building racial literacy through storytelling, mindfulness, and healing.

Rooted in over 35 years of research by Dr. Howard C. Stevenson at the University of Pennsylvania, our work guides individuals and institutions to reclaim their stories, reduce identity-based stress, and step into authentic inclusion—not as a checklist, but as a way of being.

Produced and edited by Peterson Toscano.

Mindful moment music by Dwight Dunston.

Music by Epidemic Sound.

Podcast site: storiesthatstay.net

Hosts: Shamm Petros and Dwight Dunston